-

Naval Surgery of the 18th Century.

Naval Surgery of the 18th Century.

The surgeons of the Royal Navy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were obliged to procure their own instruments before taking up post on ship. The Company of Surgeons (Royal College after 1800), as well as examining surgeons for their fitness to practise in the Royal Navy, was granted the privilege of examining the surgeons' instrument chests. This privilege was originally bestowed by Charter of Charles I and it was an honour that was jealously guarded by the Surgeons. They fought off an attempt to hand this duty over to the Surgeon and Physician of Greenwich Hospital in 1715 and once again in 1795. When the Company became the Royal College of Surgeons in 1800, they retained this ancient honour; but the Navy Regulations of 1805 no longer mention it, and when the College ceased this practice is not clear. Royal Navy Regulations of 1731 stated that, after examination, the chest was to be locked ‘and the seals of the Physician and of the Surgeons' Company to be affixed thereto in such a manner, as to prevent its being afterwards opened, before it comes on board; nor is the Captain to admit any Chest into the Ship without these marks upon it’.

The purpose of this examination was twofold. First, it ensured that the surgeon had the correct instruments and these were of sufficient standard to cope with the variety of procedures encountered during a long sea voyage. Second, the seals prevented the surgeon from selling or pawning any of the instruments to recoup some of his capital before boarding the ship. The pay of the Navy surgeons was meagre and they were unlikely to be able to afford fine sets of matching instruments. A capital set of instruments, sufficient for most procedures, cost between 18 and 25 guineas at this time (Crumplin MKH, Personal communication). Full surgeons were paid £5 a month and the pay for assistant surgeons and surgeons' mates was between £2 and £3 a month. Since the time of Charles I, an allowance was granted to the surgeon to buy instruments and medicines; in 1781 the allowance for a senior surgeon was £62. This was hardly sufficient to provide the instruments and adequate medicines for the whole crew on a long sea voyage. The poorly paid surgeon would fulfil his duty as cheaply as possible, gathering together instruments of varying makes and quality. After 1805, the medicines were provided by the Navy but the surgeon still had to buy his own instruments. This was not the case for Army surgeons during this period; each company purchased an instrument chest for its surgeon.

The list of instruments in Box 1 dates from 1812. It was provided by Messrs Evans and Co, Old Change, London, and was presented to the College of Surgeons for approval. The College suggested removal of the lenticular and the tobacco from the apparatus for restoring suspended animation, and also the ‘probe scissors’ since they were ‘improper to be used in any operation of surgery’.

List of surgical instruments which were to be included in the naval surgeon's chest (Supplied by Messrs Evans & Co, c. 1812)

Using this list as a guide, I attempt in this article to bring together the instruments carried on board ship by surgeons in the era of Nelson. These instruments are not all from a single matching set but are by a variety of makers and of varying dates and quality and therefore mirror those bought and used by the surgeons. The instrument list of Evans and Co falls easily into distinct parts according to purpose—amputation, trephining, drainage of fluid, dentistry, probing of wounds and other minor procedures, bleeding and cupping, and miscellaneous. Although this classification is to some extent my own, complete instrument sets, particularly from a little later, in the mid-nineteenth century, are often arranged and described by operation.

AMPUTATION INSTRUMENTS

Amputation was, like trephining, termed a ‘capital’ operation—an indication of its considerable mortality. It was one of the few major operations the naval surgeons were called upon to perform. The dangerous working conditions of the wooden sailing ships as well as bloody sea battles provided the surgeons with plenty of limb wounds. Avoidance of sepsis was paramount, but even so amputation was the last resort. Amputation of a limb with speed and efficiency was the measure of a naval surgeon. When bemoaning the skills of his surgeon, Sir William Dillon said, ‘although an excellent scholar, being nearsighted with a defect in one of his eyes we did not place much reliance in his abilities at amputation’.

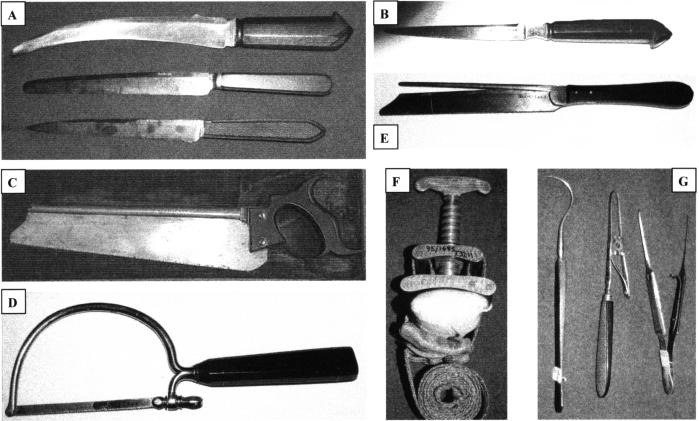

The technique of amputation at this time can be seen by examining the amputation knives in fig 1A. While the assistant retracted the skin proximally, a circular sweep was made through all layers of flesh to the bone which in turn was divided with a saw. The top knife is the oldest, dating from the end of the eighteenth century. The curve of the blade lent itself to the sweeping motion of the knife as it was carried around the limb to cut down to the bone. This curve gradually diminished over the early part of the nineteenth century, as can be seen by the later knives below. The curved style was maintained for longer by English instrument makers than by Continental makers. The top knife also demonstrates the typically English spur on top of the blade against which the thumb was placed. The middle knife demonstrates, by its rounded end, that a circular cutting motion was used rather than the later stab and slice motion, popularized by Liston. The lowest knife would be more suitable for this later technique. The catlin in Figure 1B was a double-edged blade that was used for cutting between the tibia and fibula or between the radius and ulna. It was also useful for fine work such as around the fingers.

Figure 1

Instruments for amputation. (A) Amputation knives, from top, late C18th curved, English, early C19th, less curve, blunt tip, early C19th, straight blade; (B) catlin or interosseous knife; (C) tenon saw by Laundy; (D) Benjamin Bell pattern metacarpal bow ...

Saws for amputation were generally of the tenon type in British ships; the stout blades were less likely to break (Figure 1C). Bow saws were more common on the Continent. The list from Evans and Co describes saws provided with spare blades. This suggests they were of the bow saw type. The bow saw in Figure 1D is a contemporary metacarpal saw. The tenon saw equivalent is shown in Figure 1E.

Not all severe injuries ended in amputation. John Evans, a 20-year-old seaman, was one of a boarding party from HMS Lion attacking a Greek ship. He was shot through both hands: ‘... in the right the ball entering the back part of the hand passed in an oblique direction and shattered the metacarpal bones of three fingers making its exit through the palm—in the left the shot entering nearly at the articulation of the first phalange of the thumb with the trapezium passed quite through and totally destroyed the joint—having splintered all the bones of the thumb it passed out between it and the forefinger’.

The surgeon of the Lion, James Young, ‘extracted all the loose portions of the fractured bones reduced as nearly as possible into site all the fractured ends of the metacarpal bones—Applied simple dressings with proper splints and bandages’. When discharged back to duty he was ‘quite recovered except the use of his left thumb. A proper Anchilosis having formed in the joint’.

The Petit type of screw tourniquet is seen in Figure 1F; six of these were provided to stem bleeding as patients waited for the surgeon to amputate. The cloth strap is thrown around the limb and the screw tightened, compressing the limb between the two leather and cloth pads. An extra 20 yards of cloth was separately provided for tourniquets. At the assault on Tenerife (1797), Nelson's life was undoubtedly saved by the action of his nephew Josiah Nesbit in quickly throwing a tourniquet around his right arm. Sir Gilbert Blane advised that officers should carry tourniquets in their pockets during battle, and Turnbull thought all sailors should be taught the technique.

Haemorrhage during amputation was arrested by grasping the vessel with the hook-like tenaculum (Figure 1G, left) or forceps (Figure 1G, right) and throwing a silk ligature around it. The forceps are from the collection of Joseph Liston but originally belonged to his father-in-law James Syme and therefore date from the period under review. Those in Figure 1G, centre, work on a spring design and can be left on the vessel, thus freeing the hands to tie the ligature. This model was described by Assalini of Milan in 1812.

A description of the amputation of a leg by surgeon George McGrath of HMS Russel (at the Battle of Camperdown, 11 October 1797) demonstrates the risk to the surgeon as well as the patient: ‘... he was laid on the table and the operation performed in the usual way which he bear very well indeed so much so that he did not require an assistant to hold him on the table, lucky it was that he bare it so well, as a shot at this time came into the cockpit and passed the operating table close, this startled all the women who formed the chief of my assistance’.

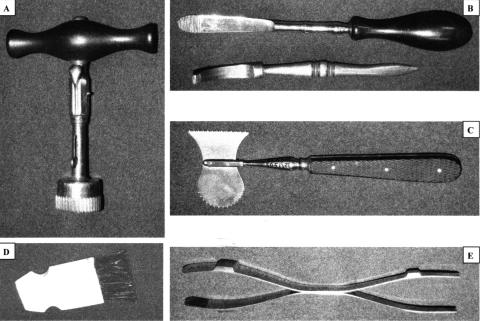

TREPHINING

Trephining, the second capital operation, was performed in an attempt to lift a compressed skull fracture or to drain an intracranial haematoma (although the latter may have been more by luck than design). English surgeons at this time tended to use the hand-held T-bar type trephine rather than the brace and bit favoured by the Continental surgeons, which was adopted later (Figure 2A). The brain could be pushed away from the wound by the smooth underside of the elevator (Figure 2B, top) or the rugine (Figure 2B, bottom), which also rasped the rough surface of the bone. The lenticular (banned by the College of Surgeons) also pushed the brain down but had a sharp edge and could be hammered across the skull to cut it. A safer alternative to this was Hey's saw, which could be used to open the skull or broaden a burr hole (Figure 2C). The little ivory-handled brush was used to keep the bone dust away from the operative field (Figure 2D). The spring forceps were used to lift the trepanned disc of bone and any fragments of fractured skull out of the brain substance (Figure 2E).

Figure 2

Instruments for trephining. (A) T handle trephine; (B) cranial elevator and bone rasp; (C) Hey's cranial saw; (D) ivory bone brush; (E) double-ended spring forceps. [Reproduced by permission of the Royal College of Surgeons of England]

DRAINING OF FLUIDS

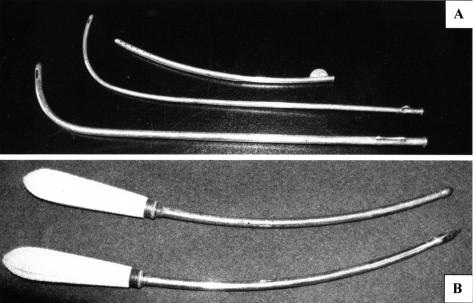

Genitourinary disease was rife in the Royal Navy in the time of the Napoleonic War. Sexually transmitted infection led to the development of urethral strictures and, because of this or prostatic or stone disease, difficulty in passing urine or retention was common. Instrumentation of the urinary tract, however, was approached cautiously; conservative treatment with warm baths and poultices was tried first. Passage of bougies down the urethra was usually attempted before catheterization. For some reason, bougies are not listed by Evans and Co.

On 27 July 1798, the 30-year-old seaman Graham, a supernumerary of HMS Albion, developed urinary retention. The surgeon, William Dingwell, passed a urethral bougie and he was able to urinate again. He was discharged onto a hospital ship moored in the Thames off Sheerness for further treatment. Marine private James Bumford, 24, of the Achille, however, required catheterization. A mess of four had all experienced the same symptoms and the surgeon, Mr Laughlin, believed he had food poisoning. To relieve his ‘suppression of urine... the Catheter was introduced—about a pint of red discharge passed of which relieved him very much’. Catheters at this time could be made of silver (Figure 3A) or of gum elastic which was introduced around 1782. John Gray, the surgeon of HMS Alfred, stationed off Cadiz, was unable to pass either bougie or catheter into marine John Brimmer after an episode of blunt abdominal trauma. Brimmer presented on 13 June 1811 and on 16 June, after several attempts to pass a bougie, Gray was forced to insert a suprapubic catheter. He ‘perforated the bladder above the pubis and drew off pints of urine’. Sadly, the marine died on 21 July. On opening the body, Gray found ‘bladder inflamed and mortified scrotum and urethra gangrenous’; probably this was a case of Fournier's gangrene.

Figure 3

Instruments for draining fluid. (A) Silver catheters, female (top), two male; (B) ivory handled trocars. [(A) is from author's collection; (B) reproduced by permission of the Royal College of Surgeons of England]

Trocars were included in the surgeon's set (Figure 3B), and paracentesis of the bladder was described by three routes in William Northcote's The Marine Practice of Physic and Surgery, 1770. The puncture could be made above the os pubis, ‘in the place where the operation for the stone is performed’ (and this was the preferred and safer route), or ‘in that part of the perineum which is wounded in cutting by the greater apparatus’ (i.e. the Marion method for cutting for the stone). The third route Northcote quotes for completeness but does not favour is via the anus or vagina. This method he makes clear is not his but that of M Flurant of Lyon, France.Of the two trocars in the set, the curved trocar would be required for the latter two procedures.

The trocar could also be used to drain fluid from elsewhere—for example hydrocele. Hydroceles were commonly recorded: sometimes they were due to trauma, from sliding down a back stay (rope from the mast); often they were infective, associated with venereal disease, when they were called ‘hernia humoralis’.

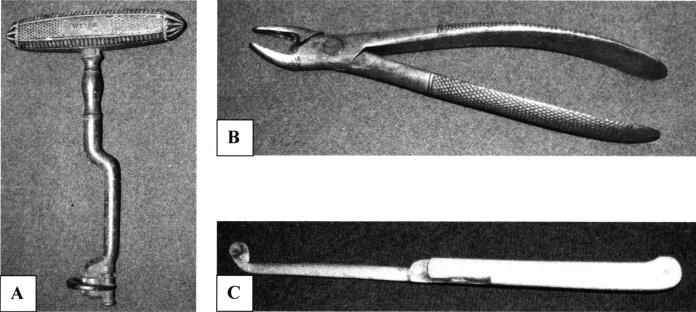

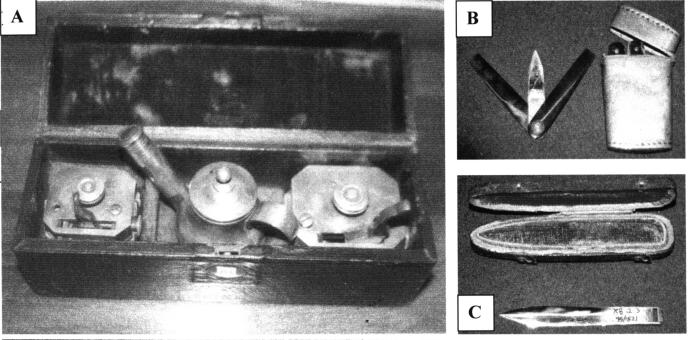

DENTISTRY

The surgeon was also at this time obliged to perform any dentistry required. The poor diet of the sailors led to poor dental condition. Scurvy, although known to be preventable, was still not uncommon aboard. The tooth key illustrated in Figure 4A is a little younger than this period but would be of similar design. The gum lancet in Figure 4C was used for draining gum-boils as well as for therapeutic bleeding within the mouth (see below).

Figure 4

Dental instruments. (A) Tooth key, by Weiss; (B) tooth forceps; (C) ivory handled folding gum lancet. [(B) Reproduced by permission of the Royal College of Surgeons of England]

PROBING WOUNDS.

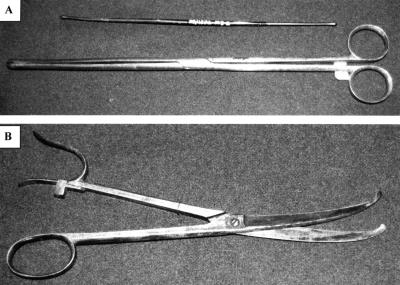

During a sea battle at this time there were many flying missiles. As well as cannon balls and chain shot (used to destroy rigging), which caused massive wounding, smaller missiles such as musket and pistol balls and grape shot (an anti-personnel weapon) could lodge in the body. A hit by a large ball to the ship would also send wooden splinters of varying sizes flying around. Wounds containing foreign material had to be explored and the pieces removed. Probes were used (Figure 5A, top) and probe scissors (Figure 5B), although frowned upon by the College, could be used to explore deeper. Balls and other debris were grasped and removed with bullet forceps (Figure 5A, bottom) or a scoop. Nelson was killed by a musket ball fired from the mizzen-top of the French ship Redoutable. It passed transversely through him, entering the left chest and lodging in the spine so that Beatie, his surgeon, was unable to remove it.

Figure 5

Instruments for probing wounds. (A) Bullet probe (top) and bullet extracting forceps; (B) probe scissors. [(B) Reproduced by permission of the Royal College of Surgeons of England]

BLEEDING AND CUPPING

At this time bleeding and cupping were performed for a multitude of ailments. Bleeding was particularly recommended for inflammatory conditions and was a remnant of the Hippocratic humoral theory of medicine.

Venesection, with a thumb lancet (Figure 6B), opened a vein and drained 20-30 ounces (600-900 mL) of blood. Ableseaman Peter Ring of HMS Etna reported to the surgeon James Campbell with a swollen testicle after injuring himself whilst furling the mainsail. Campbell cured his patient with purges, fomentations and bleeding.

Figure 6

Cupping and bleeding instruments. (A) Cupping set with scarifiers and kettle; (B) lancet and case; (C) seton needle. [(A) reproduced by kind permission of Dr Douglas Arbittier [www.medicalantiques.com]; (B) and (C) by permission of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Counter-irritation by scarifying the skin was also employed. Irritation by cupping could be dry (raising a blister) or wet (the cupped skin was made to bleed first). The set in Figure 6A includes scarifiers to abrade the skin for wet cupping and a kettle to create a vacuum within the cups. Cups were of glass or horn. Able-seaman Owen Davis presented with ardor urinae (difficulty in passing urine), haematuria and suprapubic pain. He was treated by blistering over the bladder and in the perineum. At 27 years old the probable aetiology of his symptoms was venereal disease—especially since his ship, HMS Alkmaar, was refitting in port at the time.

Counter-irritation could also be produced by means of a seton needle (Figure 6C). Passed through a superficial area of flesh, it was used to leave a silk suture which was tightened and gradually worked its way out. Today a seton can be used to cut out a perianal fistula, but the reasoning behind its use has considerably changed.

OTHER INSTRUMENTS

The surgeon was required to carry a set of pocket instruments at all times, whether on duty or off. This rule was instituted in 1799 by Earl St Vincent and remained in Royal Navy regulations until the First World War. The lancets in their neat case were often also carried. Sets of pocket instruments vary but Box 2 details the required pocket instrument set for the Royal Navy surgeon as described in the Weiss instrument catalogue of 1863. The contents of the green shagreen pocket case of Robert Liston, who became MRCS in 1816, are somewhat smaller and are listed in Box 3.

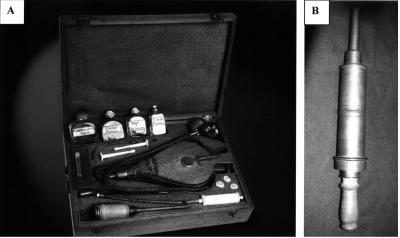

The apparatus for restoring suspended animation (Figure 7A) was still on the list of required instruments in the 1863 Weiss catalogue. Greatly promoted by the Royal Humane Society, it was used to pump stimulating infusions into the lungs or rectum of the drowned or near drowned. The tobacco in it, however, was thought dangerous by the College.

Figure 7

Miscellaneous instruments. (A) Apparatus for restoring suspended animation; (B) clyster syringe. [(A) reproduced by permission of the Bedford Museum, (B) the Royal College of Surgeons of England]

The pewter clyster syringe in Figure 7B was used to give the frequently prescribed enemas. To maintain regularity of the bowels was an important part of patient management. The syringe could also be used for flushing out the urethra in venereal disease. Mercury solution was used to irrigate the urethra and bladder in cases of lues or syphilis. Probands were sponge-holding devices. They have been particularly described for use in the throat, but could be used as swabs for other areas.

Box 2 Pocket instruments for supply to army and navy surgeons by J Weiss & Son, 1863 (Ref.

- Double bistoury, curved

- Double bistoury, straight

- Small straight bistoury

- Double edged scalpel

- Liston's needle and tenaculum

- Straight scissors

- Spring forceps

- Liston's tenaculum

- Director and aneurysm needle

- 2 probes

- Caustic holder, with grooved needle

- Vaccine instrument, with fine glass tubes

- Female catheter

- 12 suture needles

- Skein of silk

- Silver wire and needle

Box 3 Instruments in the pocket case of Robert Liston.

- 3 scalpels

- 2 hooks

- 3 bistouries

- Double tenaculum

CONCLUSION

The surgical armamentarium has changed remarkably little from the time of John Woodall's book The Surgeon's Mate (1617), through the period of the Napoleonic war under review here, to the basic surgical set of today. Surgeons require the ability to grasp and cut through tissue, sinew and bone, to secure vessels and to close wounds. They need equipment to access body cavities such as the head and organs such as the bladder. Some things have gone, such as the instruments for bleeding and cupping, and many new things have appeared. However, many of the basic surgical tools of the Navy surgeon of Nelson's time differ from those of today only in the material of which they are made.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the generous help of Mr Michael K H Crumplin and of Mr John R Kirkup, Honorary Curator of Instruments, Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Articles from Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine are provided here courtesy of Royal Society of Medicine Press

(Original source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1079363/)

Bligh.

Last edited by Bligh; 08-21-2015 at 08:43.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks